Chipping Sparrow

General Description

The Chipping Sparrow is a small sparrow with a slightly notched tail and--during the breeding season--a distinctive russet cap. Gray underparts and a gray rump contrast with streaked wings with two white wing bars. A clear, gray band runs across the nape of its neck, splitting the brown- and black-streaked head and back. In breeding plumage, the Chipping Sparrow has a white stripe over its eye with a dark stripe below it, a gray cheek, and a lighter throat patch. Juveniles are streaked and, while some molt earlier, most Washington birds keep their juvenile plumage through the fall migration. In non-breeding plumage, the closely related Clay-colored Sparrow is similar in appearance. The Clay-colored can be distinguished from the Chipping by a brown, rather than gray, rump, a darker face pattern, and the absence of a moustache. The two species also use different habitats, but are sometimes found in mixed flocks in the non-breeding season.

Habitat

A sparrow of dry, open forests, the Chipping Sparrow is well adapted for suburban environments, although they are less common in the suburbs in Washington than in other parts of the country. In Washington, they are found in open forest edges and clearings (especially Ponderosa pine), wooded parks, orchards, gardens, and in Ponderosa pine patches in steppe zones. They are also common in trees near agricultural fields, although in these areas, their productivity is reduced by Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism.

Behavior

Chipping Sparrows forage in flocks, except during the breeding season. They usually forage on or near the ground in open areas near cover. When foraging, they run or hop, stopping often to scratch the ground for seed. The Chipping Sparrow's song is a uniform trill. Its call is a hard chip.

Diet

The Chipping Sparrow eats mostly seeds, especially in the fall and winter. During the breeding season, they eat a number of crawling insects as well.

Nesting

Males return to the breeding area a week or so before the females, and begin to establish territories. When the females return, pair bonds form. Although monogamy is common, some males may have more than one mate. The male and female choose a nest site together, usually in a conifer, within 15 feet of the ground. The female builds the nest, a loose, open cup made of grass, weeds, and rootlets, lined with hair and fine grass. It is often situated at the outer end of a branch in a clump of needles or leaves. The female incubates 4 eggs for 10 to 12 days. The male feeds the female while she incubates. Both parents feed the young, which leave the nest 9 to 12 days after hatching. The young can make sustained flights within three days of leaving the nest, although the parents continue to feed them for about three more weeks. Second broods are not uncommon, but most pairs raise only one brood a season.

Migration Status

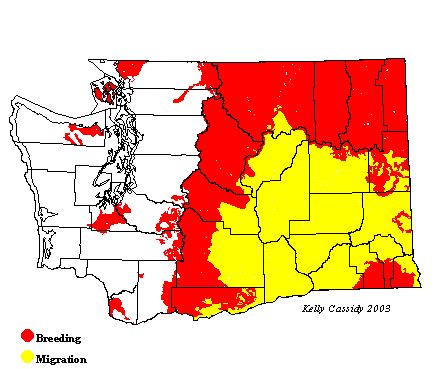

Northern populations of Chipping Sparrows (including those that breed in Washington) migrate, wintering across the southern US into Mexico. Migration is often in flocks and usually spread out over a long period in both the fall and spring. Birds leave in August on the west side, and in early September on the east side of the Cascades. Returning birds arrive in April.

Conservation Status

Although the Chipping Sparrow is still common and widespread across its range, its population has ebbed and flowed as a result of human influences. Originally, the Chipping Sparrow was probably not a common species, but may have benefited from European settlement. The population peaked in the 1850s, when it was the most common city sparrow. Since the 1900s, Chipping Sparrow populations have been declining due to habitat loss, Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism, and competition with House Sparrows and House Finches. The population is still likely to be greater than it was before European settlement. In Washington, Chipping Sparrows are common east of the Cascades, but declining in the San Juan Islands and on the Olympic Peninsula due to loss of prairie habitat and increase in Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism. According to the Breeding Bird Survey, Chipping Sparrows have experienced a significant decline statewide since 1966. The Washington Gap Analysis Project considers them an at-risk species in this state.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Chipping Sparrows are common in open pine forests and other appropriate habitat throughout eastern Washington. They are uncommon in western Washington, with a patchy distribution often closely tied to stands of oak (Quercus spp.). In western Washington, they are most commonly found around Fort Lewis and other forest clearings in Pierce, Thurston, and southwest King Counties. The open, grassy farmlands in southwest Washington provide good habitat, and some Chipping Sparrows can be seen in Clark County. Similar habitat in the San Juan Islands sustains a population that is currently common, but declining. On the Olympic Peninsula, they are uncommon from Hurricane Ridge to Dungeness. They are also found in the western Cascades at higher elevations. In other parts of western Washington, they are rare.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | U | U | U | R | |||||||

| Puget Trough | F | F | F | F | U | |||||||

| North Cascades | R | F | F | F | R | R | ||||||

| West Cascades | F | F | F | F | U | |||||||

| East Cascades | U | C | C | C | C | C | U | |||||

| Okanogan | U | C | C | C | C | F | ||||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | F | F | F | F | F | U | |||||

| Blue Mountains | R | F | C | C | C | C | R | |||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | C | C | C | C | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Green-tailed TowheePipilo chlorurus

Green-tailed TowheePipilo chlorurus Spotted TowheePipilo maculatus

Spotted TowheePipilo maculatus American Tree SparrowSpizella arborea

American Tree SparrowSpizella arborea Chipping SparrowSpizella passerina

Chipping SparrowSpizella passerina Clay-colored SparrowSpizella pallida

Clay-colored SparrowSpizella pallida Brewer's SparrowSpizella breweri

Brewer's SparrowSpizella breweri Vesper SparrowPooecetes gramineus

Vesper SparrowPooecetes gramineus Lark SparrowChondestes grammacus

Lark SparrowChondestes grammacus Black-throated SparrowAmphispiza bilineata

Black-throated SparrowAmphispiza bilineata Sage SparrowAmphispiza belli

Sage SparrowAmphispiza belli Lark BuntingCalamospiza melanocorys

Lark BuntingCalamospiza melanocorys Savannah SparrowPasserculus sandwichensis

Savannah SparrowPasserculus sandwichensis Grasshopper SparrowAmmodramus savannarum

Grasshopper SparrowAmmodramus savannarum Le Conte's SparrowAmmodramus leconteii

Le Conte's SparrowAmmodramus leconteii Nelson's Sharp-tailed SparrowAmmodramus nelsoni

Nelson's Sharp-tailed SparrowAmmodramus nelsoni Fox SparrowPasserella iliaca

Fox SparrowPasserella iliaca Song SparrowMelospiza melodia

Song SparrowMelospiza melodia Lincoln's SparrowMelospiza lincolnii

Lincoln's SparrowMelospiza lincolnii Swamp SparrowMelospiza georgiana

Swamp SparrowMelospiza georgiana White-throated SparrowZonotrichia albicollis

White-throated SparrowZonotrichia albicollis Harris's SparrowZonotrichia querula

Harris's SparrowZonotrichia querula White-crowned SparrowZonotrichia leucophrys

White-crowned SparrowZonotrichia leucophrys Golden-crowned SparrowZonotrichia atricapilla

Golden-crowned SparrowZonotrichia atricapilla Dark-eyed JuncoJunco hyemalis

Dark-eyed JuncoJunco hyemalis Lapland LongspurCalcarius lapponicus

Lapland LongspurCalcarius lapponicus Chestnut-collared LongspurCalcarius ornatus

Chestnut-collared LongspurCalcarius ornatus Rustic BuntingEmberiza rustica

Rustic BuntingEmberiza rustica Snow BuntingPlectrophenax nivalis

Snow BuntingPlectrophenax nivalis McKay's BuntingPlectrophenax hyperboreus

McKay's BuntingPlectrophenax hyperboreus